| George Catanach |

| c. 1733 - 28th May 1821 |

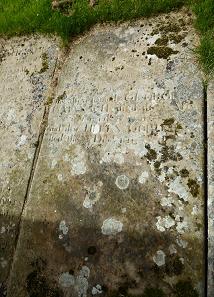

Catanach family gravestone, Kildrummy Churchyard

Find a Grave

| George Catanach |

| c. 1733 - 28th May 1821 |

Catanach family gravestone, Kildrummy Churchyard

Find a Grave

The preponderance of evidence suggests that ‘Catanach’ was favoured during George’s lifetime but he was routinely

recalled as ‘Cattanach’ thereafter; his surname was engraved as ‘Cattenach’ on his gravestone.

Captain Douglas Wimberley’s study, Notes On the Family of Gordon of Terpersie with a Table of Their Descent, refers to ‘Geo. Cattanach in Mossat, Kildrummy’ and in his 1894 study, Memorials of Four Old Families (p. 111), states that, prior to his marriage, George, a Roman Catholic, had trained for the priesthood.

George married Helen Gordon in 1757, at Gartly, Aberdeenshire. The Gartly (Aberdeenshire) Parish Register records:

1757 George Cattanach & Helen Gordon (illegible word) gave up yr. names in marriage & were married July 5.th

The Catholic Parish Register for Huntly, St Margaret’s, records the same event, crucially identifying the bride as a daughter of ‘Terpersey’:

1757 July ye 5th I Mr John Gordon join’d in the holy bonds of Matrimony before Several witnefses George Catanach in Coleatly with Hellen Gordon youngest Daughter to Terpersey

Bulloch attributes the following statements to George’s grandson, the Rev. Harry Stuart, Minister of Oathlaw, in House of Gordon, Volume II (p. 132):

Helen Gordon was reckoned the beauty of the district, which the romance of her father’s life and her family no doubt enhanced. At all events my maternal grandfather, the recognised chief of a large branch of the Clan Chattan and the most spirited youth of those rough and romantic times, hearing of her beauty and the sufferings of her family in the wreck of the civil war, made suit and won her.

Bulloch continues (p. 132):

Helen Gordon married George Cattanach (1733-1821) in Drumnahive and then in Mossat, Kildrummy, son of John Cattanach; tenant in Bellastraid, Logie Mar, whose other son John married the daughter of “Lumsden of Corrachree,” probably the John Lumsden who married Agnes, daughter of John Gordon of Auchlyne (Scottish Notes and Queries, second series, vol. iv., p. no). George Cattanach is dealt with in Harry Stuart’s Agricultural Labourers, as they were, are, and should be (second edition).

‘George Cattanach in Drumnahive, brother-in-law to the said Mary Gordon’, is named in the marriage contract

between Patrick Wemyss and Mary Gordon, daughter of Charles, VI of Terpersie,

concluded at Collithie on 1st December 1761 and recorded at Elgin on 8th November 1786, both

as a witness and a sort of trustee to the anticipated children of the union.

An account issued to ‘Mr. George Catanach & others’ has been preserved:

Together with his brother-in-law Peter Wemyss, George Catanach was one of two executors nominated in the

Last Will and Testament of his sister-in-law,

Margaret Lindsay MS Gordon in 1805, at which time he was living at Bridge

of Mossat. George was also named as a beneficiary; the will expressly provided that certain legacies were to be

postponed and that he and his wife, or the survivor of them, were to receive the interest thereon during their

lifetimes. It was also provided that any residue after the payment of the legacies fell to be divided equally

between the executors. However, it is unlikely that this latter provision was ever implemented, as in the event

there proved to be a deficiency in the sums realised.

In the capacity of executor, George Catanach received a letter from the

Rev. Roger Aitken, dated 8th August 1806, acknowledging

a sum of money paid in respect of bequests in favour of Mr Aitken’s children.

Five receipts issued to George Catanach, for payments made, on various occasions between 1806 and 1819, have also

been preserved:

The reminiscences of the Rev. Harry Stuart, alluded to in Bulloch and as contained in

Agricultural Labourers, As They Were, Are, and Should Be, In their Social Condition,

published by William Blackwood & Sons, of Edinburgh and London, in 1853 (1854 reprint), cast considerable light upon

George Cattanach’s life and the times in which he lived. The following sketch appears at pp. 5-7, with associated

footnote:

Account relating to payment for goods owed by George Catanach and others, Aberdeen, 19 July 1804

Roger Aitken to George Catanach, 08 08 1806

11 07 1806

Besides having been, for a number of years now, the minister of a parish, the whole of which has gone through all the changes of farming, and of profit and loss upon it, that any district can go through ; - in my boyhood, even, from the tales of a grandfather, who lived, in the full vigour of his mind, to a patriarchal age, and who, just a hundred years ago, with the best education of the times, and on the wreck of the property of his father and friends, who were involved in the troubles of those times, commenced farming on a large scale * - (p. 6) from him, and from others of nearly the same standing (some of them spirited proprietors, bringing things over from the old to the new school), I acquired in my school holidays from town, and do still retain, a very distinct picture of what farming and what the condition of farm labourers was in those days ; for it was a never-failing subject of conversation with these venerable worthies, and whose fine, and kindly, and polite spirit has so impressed me, that I cannot pass them even now without thus noticing it to you. But, truly, the picture our grandsires gave of agricultural life, and of its ways and means, and its comforts, in their time, was any thing but a cheering one, and they appeared to hail with delight the dawn of our modern improvements and progress. There was then in farming life, among all its members, it is true, what is much awanting in it now, plenty of good-fellowship and friendship, and plenty of leisure time to cultivate this social spirit, as well as a higher and holier spirit with it; but there was, withal, a lamentable, and to us now-a-days an (p. 7) unbelievable, penury of almost every thing else that is earthly, and which renders mortal life comfortable. Their houses, their clothing, their dietary, were generally of the very poorest and worst description. Very many of their infants could not come through the great privations their parents were subjected to, and whole families were often cut off together, on the very threshold of manhood, by agues and consumptions, by small-pox, and other epidemics, without having any means tried to save them. It is true their work was not either very constant or very heavy, but then the fruits of their labours were just as scanty and precarious. Every alternate harvest was then, from bad husbandry, a late one ; and a late and bad harvest not only brought a scarcity, but even a famine upon the land ; and, except for the kindly give-and-take way, and the never-move way, in which employer and employed in general lived together, the state of their other comforts seems to have been wretched in the extreme. * He was not originally intended for farming, but for the Roman Catholic Church, as a priest, having four uncles in that office. They all were involved in the troubles of 1745, and had to flee the country ; so that I have often heard him (p. 6) say, in joke, that “the Prince made him heir to six relatives all in one month, at seventeen years of age, and he could not help, therefore, wishing him well.” Colecting (sic) the debris of the wreck of what his relatives had, and falling in love with a neighbouring laird’s daughter, whose father and brothers also spilt their blood and lost their all in the “cause,” he abandoned the church for the plough, taking things very easy as to bullocks, but not as to books – and his books were no joke, either as to matter or as to language. He used to tell myself, when I grumbled that the schoolmaster would give me no explanation of the Latin, how easy the way we now took to learn it, from what it was in his day – Ruddiman’s Larger Grammar committed to memory, to begin with, and not a word spoken in the school but Latin. He was totally blind the last ten years of his life, but it never affected his cheerfulness, which was great indeed. I have often heard him say, that he would not now like to “see,” as he could only see things to vex him. I have often awakened at two and three in the morning, and heard my aunt finishing off Sir Walter Scott’s last. She would sometimes stop and say, “Now, father, there’s just all our friends o’er again.” “Tush Betty, read on, will you? Sir Walter kens a’ about them as well as you do, and tells about them a vast deal better.” There were many such farmers then as he, reading their T. Livy to their breakfast, and having a tilt at the fencing foils in the evening with the young fellows. I might have given a “sample” of others, but from grateful feelings for the stimulus he gave to my very early and very hard way at school of fitting myself for my present office, and to give my observations the more weight on the farming of those times, I cannot help alluding more especially to him. After the fashion of the times, he kept open house, and I heard all the good and the bad of the old and new schools just opened, discussed a thousand times over by his visitors, many of them retired farming officers, who had seen much in other countries, and in a rough enough way, and who did a great deal in spiriting on improvements.

The aunt referred to, Betty, can confidently be identified as

Elizabeth Catanach.

A further anecdote is included in a footnote, at p. 69:

I well remember hearing my grandfather often tell how, when taking a near cut through the Grampians by Lochlee, home to the north of Aberdeenshire, he lodged a night with Ross, the schoolmaster of that parish, and the poet of that glen, being his kinsman. Ross started next day with him, to convoy him over Mount Keen ; and to beguile a resting hour, at the foot of this very steep mountain, when they had crossed it, Ross, with great hesitation, pulled a paper out of his pocket, and read it to my grandfather. It was a poem he had composed in English verse. When he had done reading – “Your poem,” said the traveller, “Mr Ross, is “delightful, and you are nearly as good at the English as you are at the Latin” (Ross being a first-rate Latin scholar, and no bad poet in it too). “You are trying, I see, to imitate some of these great English poets ; but it will not go down just yet to speak of Scotch fashions to Scotch people in the English tongue. Gae away hame, man, an’ turn it into braid Scotch verse ; and gin ye print it, the not a jot will my lassies do at their wheel, and some thousands mair like them, till they have read it five or sax times o’er.” The poet took his advice, and this poem turned out to be the once popular “Fortunate Shepherdess.” Men and women in all classes then seemed fond of poetry. I recollect well once, rummaging through a mass of old papers in some of my grandfather’s drawers, when I came on a great number of songs and ballads, &c., written by his ploughmen, and dedicated to him as their master. Almost nothing worth speaking about happened in a district then, but some half-dozen men and women must chronicle it in rhyme, after their own fashion, and all the country-side must commit their effusions to memory. If this did no farther good, it exercised the intellects of some and the memories of all ; and the not a few that I have seen in manuscript (printing then was never thought of), and heard recited or sung, seemed very chaste, and to have no “small wit” besides.

George died on 28th May 1821, as attested by the inscription upon the family gravestone, transcribed by Andrew Jervise, F.S.A. Scot., in Epitaphs & Inscriptions from Burial Grounds & Old Buildings in the North-Eaft of Scotland, with Hiftorical, Biographical, Genealogical, and Antiquarian Notes (Edinburgh: Edmonston and Douglas, 1875), at p. 266, in the section devoted to Kildrummy.

|

|

It would be interesting to know whose child George Gibb was. Was Gibb his middle name or surname?

The question of the legacies reserved from Margaret Lindsay MS Gordon’s

Last Will and Testament was re-ignited with George Catanach’s

passing. The burden for resolving this matter passed to George’s executor, the

Rev. Alexander Reid, assisted by George’s daughter Elizabeth Catanach,

to whom a letter was addressed by Alexander Webster on 20th August 1821; Mr Webster enquired after the

legacies in favour of Margaret Umphray and her children, which, in the meantime, had been liferented to George and

his wife, who had predeceased him. Mr Webster was probably acting in a professional capacity; otherwise his interest

in the matter is unclear. Referring to George and his wife, ‘who are both now dead’, he asked which of them had

survived the other and when the latter of them had died. It is regretted that Elizabeth’s response is not to hand,

although it is otherwise known that George had survived Helen by almost seven years.

The public roup or auction conducted on Elizabeth’s behalf at Bridge of Mossat on Tuesday, 6th November

1821, was presumably for the purpose of disposing of George’s effects:

A letter from George’s grandson, Harry Stuart, to Elizabeth Catanach, mentions a substantial sum of money apparently

due to Harry’s grandfather, presumably George, from the estate of a Mr Ritchie, not, unfortunately, otherwise known.

Alexander Webster to Elizabeth Catanach, 20 August 1821

Proceeds of Public Roup, 06 November 1821

Harry Stuart to Elizabeth Catanach, 27 December 1821